Vevey, 14 August 1943 - Amsterdam, 19 May 2022

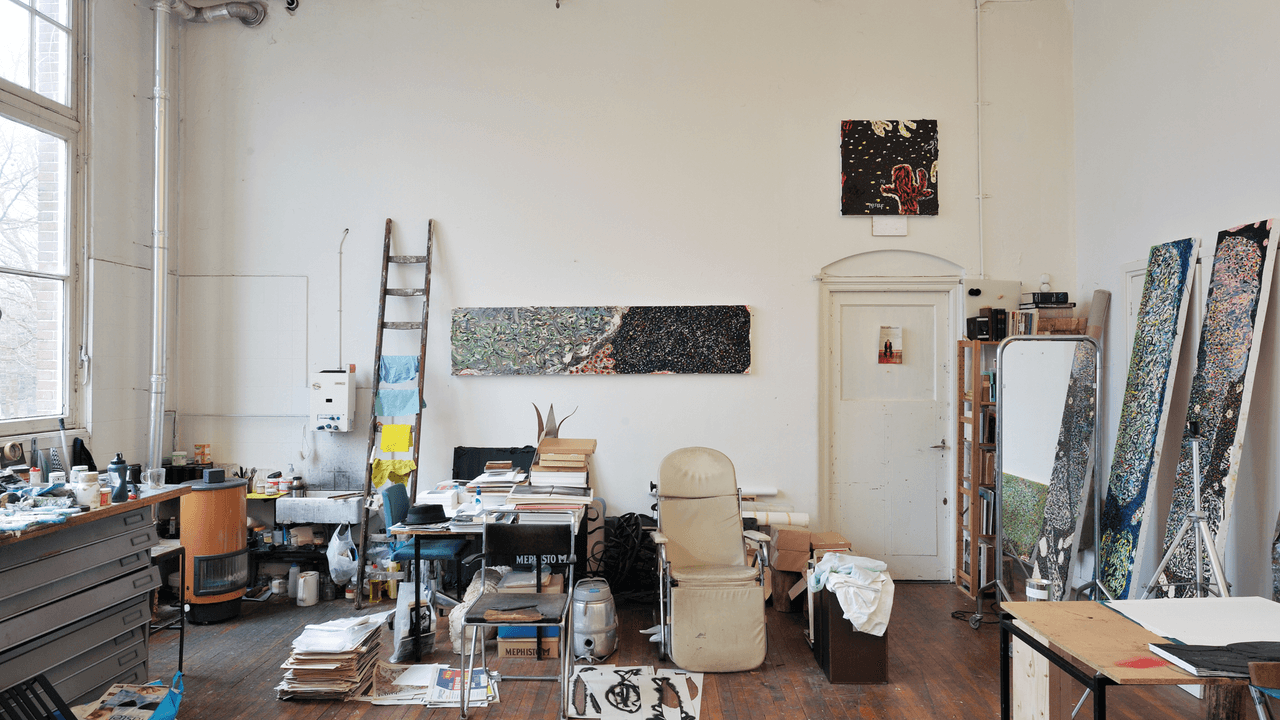

The work of Eli Content is as rich and turbulent as life itself. Not only does he produce paintings and drawings but also prints, collages, artist's books and spatial installations. The way in which these come about is equally diverse. In the late 1990s Content decided, in fact, no longer to limit himself to a single style or outlook; he wanted to embrace the boundless imagination and give expression to all of the images in his mind, in the belief that a person is more than a single thing. That decision opened up the way to surprising developments and a multifaceted body of work, which, while not aiming to please, is nonetheless seductive.

Initially, in 1976, when Content was accepted as a self-taught artist at Ateliers '63, he had no concern for visible reality as a point of departure for his work. Like the American artist Sol LeWitt he made severe, austere drawings and, later on, monochrome paintings that he composed meticulously on the basis of a grid drawn beforehand. But in terms of content there proved to be an essential difference in relation to his American colleague... Content avoided representations because, as a practicing Jew, he adhered to the second commandment not to produce likenesses of the world around him. Via abstraction he wanted to portray the world behind visible reality. The divine blueprint as the basis for creation.

But once Content abandons this idea, and curiosity gains the upper hand over dogma, his oeuvre develops like an explosion: nothing is impossible. He then paints, says Rudi Fuchs, "because through painting he wants to be able to see and discover the improbable, inimitable nuances in the visible world of color." His landscapes, trees and starry skies, such as Sterrennacht/12 o'clock and all is well (2009) are thus "true spectacles of nuance." They hover between figuration and abstraction and thereby ultimately sweep the viewer along to a deeper reality not visible to the eye. Content paints trees and eventually people, or Menschjen as he calls them, like we've never seen them before, with fiery bodies and frightful but amazing tentacles. And later he tries, in portraits, not to paint people as they appear on the street – freshly shaven and wearing white sneakers – but people as they really are: raw and unpolished, stripped of that thin layer of civilization. Robust images that Content fortifies with nails, bottlecaps and stones.

Content tends not to like speaking about the meaning of his work. He prefers to talk about his fascinations and affinities, about Roman murals, the work of Bas Jan Ader, plastic toys, skin disorders and maps of the world. About World War II, poetry (he actually wanted to be a poet), jazz music and the Kabbalah. But especially about the creation myth, that "poetic attempt to explain a mystery" which is ultimately one big source of inspiration for his oeuvre. In the highly poetic series Au Commencement (2016), in which – against a background consisting of Hebrew newspapers – he builds his own version of the creation with letters from the Hebrew alphabet, this becomes very concrete.

With his oeuvre Content has, slowly but surely, unintentionally created his own universe which he continues to augment to this day. In doing this he still frequently heads off in a new direction, as he demonstrated in his 2020 exhibition Lust for Life with a motley and brightly colored collection of cut-out figures and masks, which he had made while recovering from a severe illness.

"Creating," Content once said in an interview, "is a way of healing the disturbed universe." But for Content it is also undeniably an existential condition. In fact the freedom, independence and liveliness that his oeuvre exudes is the ultimate victory over death.

text: Esther Darley

translation: Beth O'Brien