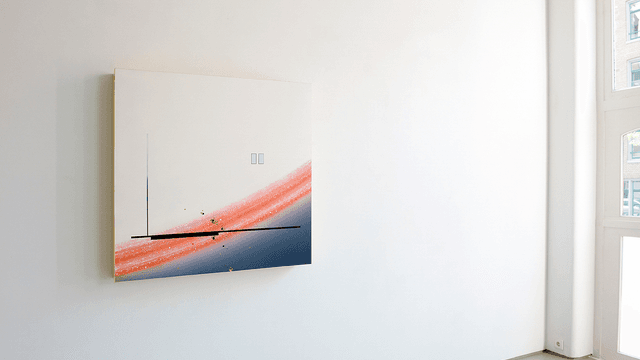

Han Schuil

Heat ll

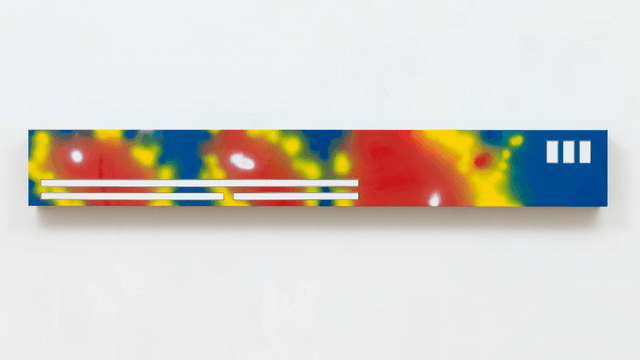

Han Schuil

Heat

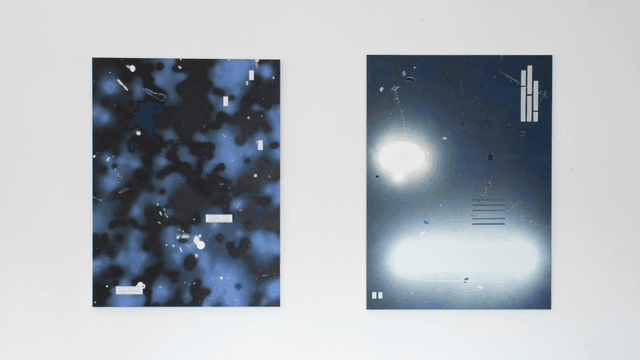

Han Schuil

Recent Paintings

Han Schuil

Blast

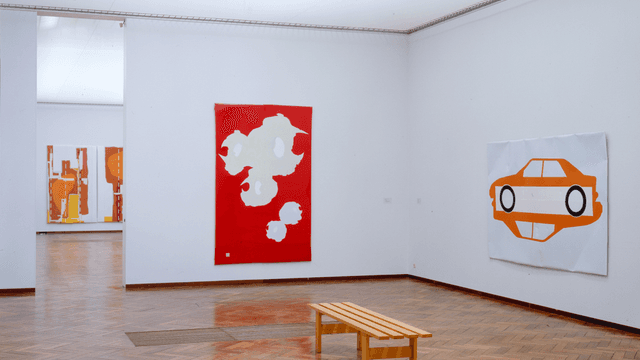

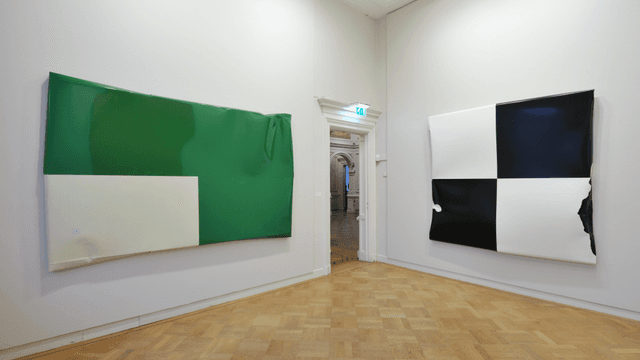

Han Schuil

Crashed and Gobsmacked

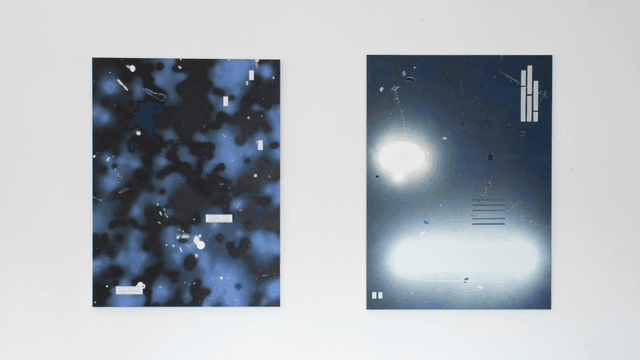

Han Schuil

Recent Paintings

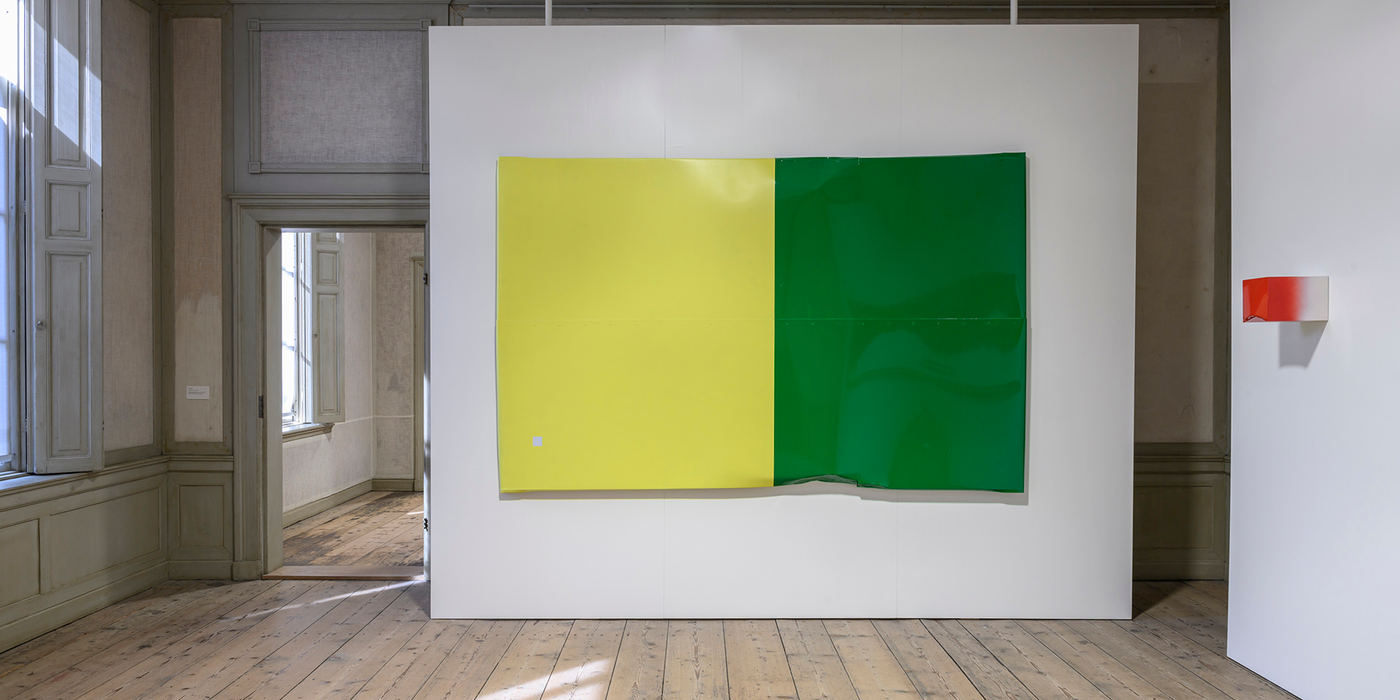

Han Schuil, Tim Ayres, Ab van Hanegem, Jan van der Ploeg

Later on We Shall Simplify Things (Andratx)

Han Schuil, Tim Ayres, Ab van Hanegem, Jan van der Ploeg

Later on We Shall Simplify Things (SCHUNCK)

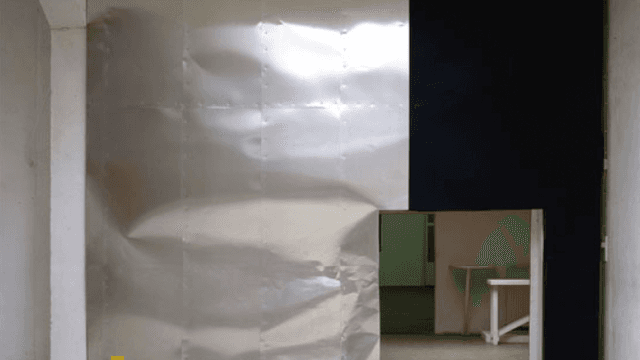

Han Schuil

Clean