Hans Hovy, Elisabet Stienstra, Arnulf Rainer, Jugoslav Mitevski, Benjamin Roth, Emma Talbot

We Can't Go Back

Hans Hovy

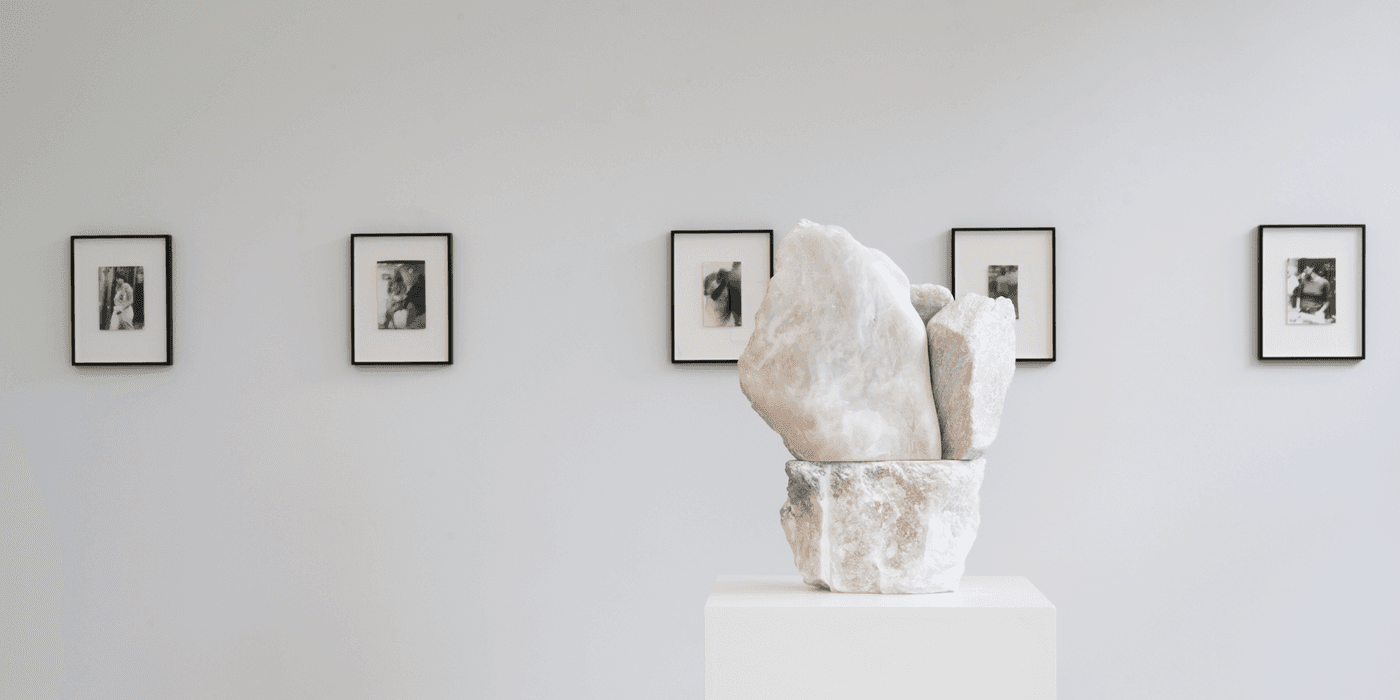

King of Sculpture

Hans Hovy

Glassobs and More

Hans Hovy

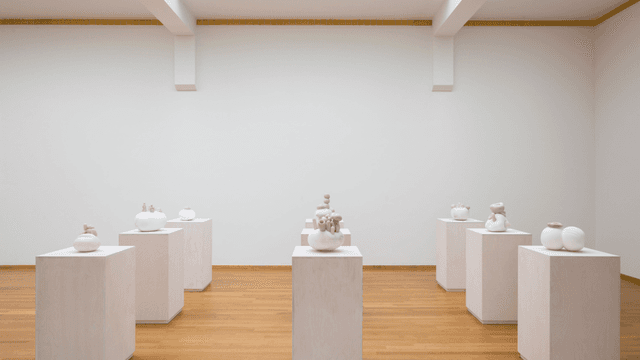

Sculptissimo

Hans Hovy

Sculptissimo

Hans Hovy

Sculpture

Hans Hovy

Kunstvereniging Diepenheim