Imagine that, with one push of a button, you could show your thoughts. A print-out of the entire arsenal of images and emotions that were shooting through you, both consciously and unconsciously. A sort of mental picture. What would that look like? The work of the English artist Emma Talbot seems to come close to this, combining memories, fears and obsessions with current events, myths and lines of poetry. Talbot depicts them in many small drawings, which she then brings together on large silk panels. Familiar situations alongside mysterious scenes. As if every drawing were a little window through which you can peer in at part of the artist’s brain.

Talbot’s workshop is located at the heart of a studio complex in London, literally in the middle of the building, without windows or natural light, without the sound of children racing past or traffic driving by. When she opens the door of her studio, she is confronted with nothing but herself. ‘When I’m working, I no longer need the outside world,’ says Talbot. ‘I have absorbed it into myself. Isolation is a good way to focus on my inner self, on memories and feelings. These are more valuable for my work than external appearance.’

On her desk is a copy of Ira Progoff’s book At a Journal Workshop, in which the American psychotherapist describes how to draw upon the subconscious in order to fathom the patterns of life. The method is intended to help readers shape the future and to get to grips with life. Talbot seems to use the book mainly to evoke clear images of the past and immerse herself in them. Personal recollections of her time at school, for example, whose setting she drew as accurately as possible from memory, or family stories involving her mother’s distress and despair as a young woman. And also classical myths, poems by T.S. Eliot and feminist philosophers such as Luce Irigaray and Hélène Cixous. All of these can serve as prompts for surprising, amusing and touching drawings, which combine to generate new stories. The pictures touch upon one another, reinforcing one another’s atmosphere, like lines of a poem. They set a particular tone, which we can all interpret in our own way without having to understand every detail. Take the work Why Do You Fear The Power Within?, in which Talbot, inspired by the Slavic myth of the witch Baba Yaga and the life of the Russian Agafia Lykova, appears to tell a story about female primal force. We see a woman transforming into a snake and another sitting with her legs apart in a hut while her flaming crotch gives birth to wisps of smoke. The enigmatic scenes are accompanied by comments such as ‘Ancient wisdom lies just behind your eyes so vivid’ – as if Talbot wishes to connect past and present – and ‘Death is part of any picture. But first we must let some magic pass between us.’ Does Talbot want to urge you to open yourself up to an invisible world, to your own intuition? Whatever the case, the seductive snake-like lines that link the scenes naturally put you in that kind of mood.

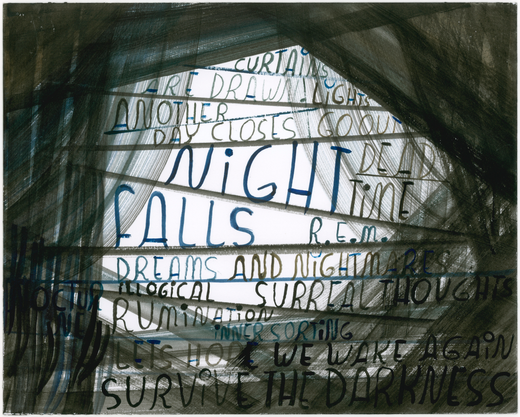

While drawing, Talbot became very conscious of the fact that the faithful depiction of reality is a construction focused mainly on outward appearances; understandable but also subjective and far from complete. Talbot prefers to look inwards, like the symbolists, who emphasised intuition and the subconscious. And just like images on medieval altars, logic and unity of time, place and space are, in Talbot’s work, secondary to the telling of her story. And what is time, in fact? You can almost hear her thinking in Time Folded when she writes: ‘Is Time folded, like origami. Old hours tucked behind the sharp creases.’ Meanwhile you are looking at a figure that appears to be emerging from her body, with several arms, like a Hindu god, fainting and at the same time walking on or looking dazed into the mirror at what time has done to her while she was not paying attention. In the background, lush flowers grow more and more sinister. With her apparently naive gaze, Talbot distances herself from the way of looking to which we have been accustomed since the Renaissance. In that sense, her work also appears to be a reaction to the post-Enlightenment era in which we are living. In a world where we want to master everything with our minds and we are all connected to our own devices, Talbot is open to the transcendental, the irrational and the mysticism of nature.

This can also be seen in the way she presents her work. Hanging loosely over copper pipes, with coloured ropes on either side, the works appear to play a role in a mysterious ritual. They seduce us, awaken our curiosity and yet at the same time they impose a certain distance. It is as if Talbot is playing with the suggestion of a higher truth, a fourth dimension, a puzzle that might just open itself up to you. In her most recent installation, Safe Space, the silk cloths form the walls of a tent. It is a colourful spectacle, reminiscent of the magnificence of Japanese kimonos – but the flipside emerges as soon as you ‘read’ the images. Among factory chimneys and bricks, plumes of smoke twist like screaming mouths, without making a sound. Flames dance against a dark sky filled with noxious gases. They encircle scenes about violence and fear while unprocessed traumas are concealed beneath a mountain of coloured lines – what Talbot wants to say is that the brain is very good at pretending nothing is wrong. What appears to be a ‘safe space’ is in fact a fragile and temporary place that offers anything but protection. This makes Safe Space a symbol of the tense and uncertain times we are living in and against which it is so hard to arm ourselves.

This is one of the powerful antitheses that constantly recur in Talbot’s work. Seductive turns out to be destructive, safety proves a farce, fear goes hand in hand with trust, and the ephemeral, light silk is full of weighty matter. This lends every image a double significance. Her interest in the irrational and in the reality that cannot be seen might suggest that Talbot’s work stands outside of time. But that is not the case. In Rhapsody on a Windy Night, she quotes T.S. Eliot, precisely because he was able to capture the bitter and ominous zeitgeist that held sway between the two world wars, a period that Talbot feels is related to our own. And a scene escaping from the large pot at the base of Pandora For Today – Plant Your Scraps Of Hope refers to Trump’s politics. ‘Art is more important than ever,’ says Talbot. ‘It gives you the opportunity to speak out.’ And so The World Blown Apart appears not only to be an attempt to get to grips with an uncertain world, but also a warning, a consolation and a message to listen to your own innerself. The freedom that Talbot offers her viewers to distil their own truth out of all the different information makes her work more current and relevant than ever.

Text: Esther Darley. Translation: Beth O'Brien