A mural + paintings

Hint of Spring

This past winter, bright days of freezing weather were few and far between. The rest of the time, it was mostly grey when you glanced outside. The news brought little relief: outbreaks of bird flu, the ongoing war in Ukraine, brutal oppression of women in Iran and Afghanistan, floods, forest fires and an earthquake that devastated large parts of Syria and Turkey. It is hardly surprising that young people – with that sense of hopelessness colouring their future – sometimes seemed so defeated. It could take less than that to make a person depressed. But as night fell during the first few weeks of the new year, the clear song of a blackbird could be heard. In good spirits, the winter-flowering jasmine bloomed and even the occasional bulb bravely poked its head above the frozen ground. It was as if nature wanted to assure us that, after that long grey winter, a spring really was going to follow.

On one of those days when the sun showed its face, I visited the studio of Robert Zandvliet, where the party had already started. The famous Flemish artist Roger Raveel (1921–2013) would have called it ‘Maartse Magie’ (March Magic), referring to the changes in the natural world between winter and spring. All around me, I saw the fresh yellowish green of new leaves, budding branches, grass glistening with frost in the sunshine.

The new series of practically sized, almost square paintings began as a form of investigation for the artist. In his most recently completed series, Le Corps de la Couleur, which Zandvliet created in the period 2019–2021, he had sought to achieve his ultimate interpretation of colour in large formats, with titles such as Ultra Marine, Yellow, Vos, Tangerine and Grēne. A new series was inspired by this last work, Grēne (old English for ‘green’). This painting consists of transparent greenish-yellow areas over which a rhythm of stripes has been applied in yellowish white and two shades of green. The work reminds me of a field of stiffly swaying grass, seen from above. The artist wants to develop this idea in a subsequent series involving large-format colour fields.

Last year, between these two series, Zandvliet practised his technique with structures and textures. When I see the fresh green explosion in his studio, I could almost imagine that he found the inspiration during walks among bushes with budding branches and lush green meadows. But nothing could be further from the truth. As always, the painter looked at his predecessors. For example, at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, he studied how the painter Robert Zünd used a rhythm of white strokes of paint to make the sun shine onto a wheatfield. Or how Augusto Giacometti used red-black paint in a very fragile way to decorate a mountain landscape with thin twigs, winter foliage and a spruce forest in the valley far below.

At the studio, on a stool beside the sofa and in front of the fire, is the book Facing Gaia, a collection of lectures by the French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour, which the artist often reads. In those lectures, Latour described how human activity and the natural world are inextricably linked, basing his thinking on the Gaia theory of the British scientist James Lovelock (1919–2022)*. In 1969, during the course of his work for NASA, Lovelock realised that the planet Earth is a self-regulating superorganism. According to this theory, everything is in constant motion with each other in an attempt to achieve balance. He called this activity or living organism ‘Gaia’, after the Greek goddess who was the personification of the Earth.

Lovelock’s theory shows affinity with the ancient Chinese classic text, the I Ching (or Yi Jing)**. Strongly related to perceptions of natural processes and phenomena, the I Ching describes a complex network in which opposites such as summer and winter, day and night, male and female, warm and cold, rain and drought, yin and yang are constantly moving in relation to each other, seeking equilibrium. This is a system in which the night always turns into the morning, and the morning slowly moves towards the afternoon. On all levels of existence, there is a natural rhythm in which opposites flow into or galvanise each other.

As the I Ching assumes that everything happens for a reason, the book was often dismissed in the West as a method for divination and fortune-telling. But this classic also forms the basis of the highly regarded Taoism and Confucianism and underlies the Chinese philosophy of the ‘five phases’ or ‘five elements’. This describes the cycles of moments of the day, linking them to the changing of the seasons and the different stages in our lives: being born, growing up, becoming older and dying. These cycles are interwoven with emotions and elements to form a complex system in which everything is connected and moving in search of balance. Summer, for example, is linked to the element of fire, to the afternoon and to our adult life. And winter stands for night and death and is associated with the element of water. When hibernation is over, nature wakes up again. This is the time of a new spring that is arriving, the time of the morning and of youth. Everything is saturated with a strong will to unfold, to discover and to grow. The element associated with this season is wood, and the colour is green. The element of wood represents an upward and outwardly focused energy, which we can see in the budding of the trees, the growing of the grass, in the sprouting of young plants.

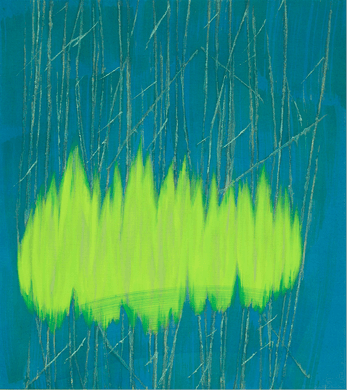

With his new series, Zandvliet offers us an allusion to that vitality. His paintings are filled with the motion of the seasons. The yellow seedpods in Le Jardin XVII resonate with the energy of the summer sun. In Le Jardin XII and Le Jardin XXI, icy blue or dry yellow branches light up in a rather watery glow, while in Reed a wintry evening sun turns reeds into yellow-green flames. Just as everything is interconnected in the Chinese teachings and in the complex living organism of Gaia, Zandvliet unites these new works with a painting in bright spring colours created directly on the wall. The entirety offers us a hint of long-awaited spring and reminds us that we are no more than a fragile link in a much greater system of forces.

Text Rebecca Nelemans

* James Lovelock, Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth, 1979. Lovelock developed his Gaia hypothesis when designing scientific instruments for NASA.

** The Book of Changes (also known as the I Ching or Yi Jing) is a classic text from ancient China. The book is one of the Five Classics of Confucianism.