The recent works of Ina van Zyl are, once again, vivid, wry and unavoidably immediate. A carnation, a glass of water, an extended foot... But also a portrait of her father and a view of a dead mosquito. Close-ups of everyday images – tangible, grand and insignificant at the the same time – which Van Zyl interconnects by way of her seductive manner of painting. What you see is what you get. Or at least that appears to be the case.

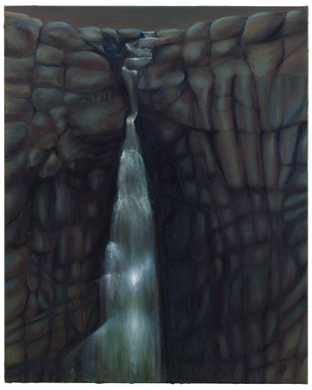

In her new exhibition In A Landscape Van Zyl shows these close-ups amid smaller landscapes based on her home country South Africa. For the first time her subject is bigger, much more vast, than the format on which she paints. She zooms out. But despite that distance she stalks the landscape, as it were, and thus gives rise to an odd tension. The face of a mountain becomes pockmarked, a boulder smooth and inviting. And deep, dark hues like those in Sneeukop (2012) cause the landscape to reveal itself only gradually.

The landscapes are more than portrayals of territory. They’re fusions of objective rendering and the connotations that Van Zyl ascribes to them. Time and again, Van Zyl’s works command associations. Her landscapes bring to mind her paintings of vaginas, breasts and toes which, despite her concise approach, assume a certain landscape- like quality. And like those vaginas, breasts and toes, the landscapes refer both to desire and to vulnerability.

Van Zyl manages to raise her subjects – a mosquito, a glass of water – from their insignificance by, literally, painting them in a grand and overpowering manner. This paradox weaves thematically through the entire exhibition which hovers between all and nothing, between life and death. Water (2014) is nothing, simply water in a Duralex glass and, at the same time, the source of all life. In Fall water splashes down lavishly from a mountain, but it also crops up again in the title of Van Zyl’s portrait of her father: What are we going to do about water?

Little Orgasm, a budding carnation, is painted so sensually that it teems with life, while the mosquito, an inconsequential insect – rendered so intently and bearing the title Mort – assumes a monumental quality. And the longer we look at Pulse (2013) the painting of a provocatively extended foot, the more it exudes death rather than joie de vivre. ‘Pulse’ being the beat of dance or jogging, life at its peak... or ‘pulse’ being an indication of the very absence of this.

Here each image has significance and is imbued with highly personal meaning. Precisely for that reason Van Zyl takes a cool and objective approach, wanting to touch on the essence by ‘painting away’ the personal. By doingso she creates a universal experience. She even attempts to achieve this in the least objective image of all: the self-portrait. Playing with darks and backlighting (‘how dark can I make it?’) she seeks objectivity in the formal approach. But in the meantime she paints herself frontally, showing no mercy, with big wide eyes. It’s as if we, as viewers, can look straight through those eyes to an inner landscape. In another self-portrait titled In A Landscape (2014) we see her reclining. That horizontal format is reminiscent of the mosquito, the foot... and landscape. But this reclining self-portrait also evokes desire, awareness and the silence that prevails throughout these works.

Translation: Beth O’Brien