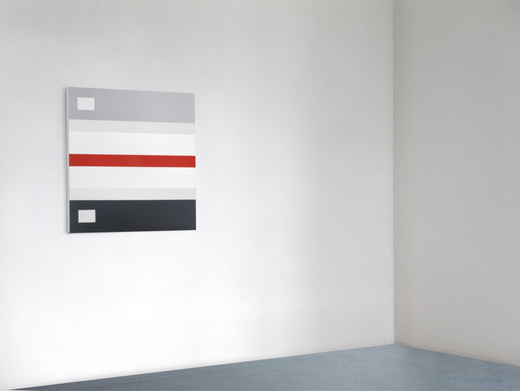

Seething away in the work of Alan Uglow is a struggle for the surface. The struggle goes on, painting after painting. That which initially comes across as being calm, simplicity, balance is misleading. Appearances are deceiving. Few painters show such a variety of surfaces, each of them different in size and tension – but always painted monochromatically. The harmony achieved by Uglow involves a great deal more than juggling things around, dividing and composing. The planes that he paints with geometric precision evidently derive their unusual tension through the effects of light, space, color, time. That is to say: through everything that arises in the world – in the observation and experience – of the viewer, on further contemplation.

Alan Uglow (Luton, 1941) can be placed within the twentieth-century development of abstract art – the art of Mondrian, Ad Reinhardt, Newman, Ryman. That holds true to the extent that it relates to the desire to tranpose visible reality into form and proportion. But then without spiritual, religious or ideological intentions. What you see is what you get. His source is the world that he perceives through the senses: that which he sees, smells, hears, feels. A stadium fence, the form of a job advertisement, a newspaper heading, a soccer field, sound.

His earliest memory of observation is from the war: the nightly raids, deafening sirens, the smell and the shape of a gas mask, fire. “It was strange to experience situations where I must have been two or three years old when I started to take in what was happening. It was an awakening that I could only give meaning to much later on.”

In 1969 he decides to leave England and head for New York. Pubs that close at eleven, a metro that stops running after twelve: why stay? London life gives way to the overwhelming new freedom and turbulence of New York. His relationship to the outside world remains intuitive; it’s never planned or strategic. That always causes him to work under great pressure and on the basis of immense inner tension that drive him on, time and again, to yet...