Intuition is like a scent: elusive, invisible and yet immediately familiar. It is that indefinable certainty, about each other and each other’s work, that has brought Odile Maarek, Diane Quinby and Ina van Zyl together. Three artists, three women, who decided both intuitively and spontaneously to do something together, ‘like people starting a band would do’.Then There Were Three is an exhibition made up solely of drawings, by artists with their own voices and rhythms, but all in the same key.

Maarek (b. 1961), Quinby (b. 1967) and Van Zyl (b. 1971) often associate people and things with an underlying world of unspoken emotions and ideas. In their work, they try to gain a grip on this world. By drawing, they delve beneath the surface to retrieve the unutterable, charging their images with tension and meaning. These are, at the same time, three artists who dare to mistrust their intuition. Because they value doubt more than certainty. Why are we here? What are we doing here? What is the meaning of things? They draw in the vain hope of finding answers because, in the words of the South African poet and singer Gert Vlok Nel, ‘Om te lewe is onnatuurlik,’ living is unnatural.

Odile Maarek

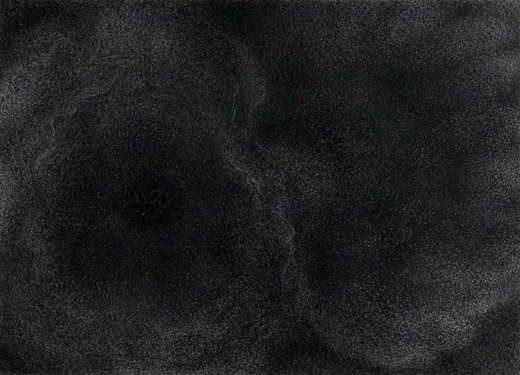

Sometimes a work of art seems like a natural phenomenon. As if no artist’s hand were involved. Georgia by Odile Maarek is one such work: a drawing of two poppies emerging from the darkness. The word ‘drawing’ does not even feel appropriate here. There are no lines or clear contours. With an infinite number of dots, she taps the crayon on the paper like a sculptor carving out the shape from the stone. Because it is precisely in the blackest black that the light emerges. Light and dark rippling through the image and making the petals appear to be gently moving in the breeze.

Maarek calls the work an ode to Georgia O’Keeffe, an interpretation of O’Keeffe’s close-up of poppies. But you could also call it an ode to Georges Seurat, who, with the help of a piece of black Conté crayon, seemed to summon up his images rather than to draw them. His soft shading and his subtle use of light and shadow, which make even the darkest drawings glow, have had a major influence on Maarek’s oeuvre. But at its core is her love of darkness.

As a child, suffering from diminishing eyesight, Maarek embraced a twilight world in which soft contours and diffuse spaces stimulated her imagination. In her predominantly black landscapes, she now offers us a similar experience. Landscapes in the dead of night that suggest measureless spaces in which you feel your way through velvety black, soft grey and undulating light. Or landscapes like the ones in the series Point Sensible, in which you become lost in a hallucinatory succession of concentric circles like dazzling clouds of mist or a sparkling starry sky. Minuscule circles are like eyes on the world or like the lenses that suddenly allowed Maarek to see the world clearly again.

Sometimes Maarek combines this soothing disorientation with a touch of surrealism by drawing over existing images. She has, for example, adapted old reproductions – from engravings by Gustave Doré to photogravures of work by Bruegel and Da Vinci – making the images merge into each other and become blacker; impenetrable as forbidden territory, but all the more attractive to approach. Maarek obscures the image in an attempt to reveal the mystery and light that lies behind it. As a viewer, you have no choice but to let yourself be carried along willingly.

Diana Quinby

Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close. Diane Quinby’s drawings have nothing to do with Jonathan Safran Foer’s bestseller. And yet their associations bring to mind the words of that poetic title. Quinby (b. 1967, New York) has been focusing on the human body for years. Over and over, she draws torsos of men and women, from the front or the back, alone or together, side by side, and usually naked. Just a little larger than life and tightly framed, these are drawings from which you cannot escape. Confrontational and familiar as a mirror image – this is what we are – while alienating and uncomfortable in their physical imperfection. At the same time, the extremely detailed way in which Quinby depicts the body in so many meticulous lines – layer upon layer – has a magnetic effect.

Consider Couple - Backs, a drawing of two torsos seen from behind. A man and a woman, unprotected and vulnerable with arms hanging by their sides like strange trunks, elbows like wrinkled knots, the spine as a straight vertical line. They take complete possession of the paper, filling it with a landscape of skin in which the minuscule, clearly defined spaces feel like places to catch our breath. But up close, alienation turns into tenderness. Then the intensely constructed soft skin mainly evokes feelings of intimacy, desire and loss.

For Quinby, drawing is a meditative process. As if, while she moves the graphite across the paper almost without thinking, she turns herself inside out. This results in drawings in which interior and exterior merge. These are drawings that are formed not only by an infinite number of fine pencil lines but also by thoughts about the ageing body, motherhood, touch and loss. Big questions and personal reflections, as subtle as they are candid. Extremely loud and incredibly close.

Ina van Zyl

A story without words. This is how Ina van Zyl describes her new series of drawings. Fifteen large charcoal drawings of flowers and portraits, feet in ballet shoes, penises and a vagina. Familiar Van Zyl images, which now assume new forms in charcoal and pastel on paper. She draws the limp leaf of an anthurium, as tender and tactile as old skin in stark contrast with the hard spike protruding from it. Or the bony face of the comic artist Wasco, which she explores like a landscape in all the shades of grey and black that charcoal has to offer. Crafted with precision and concentration, they also reveal the fun of creation and the direct nature of the material, which she also uses to mould her images with her hand.

You could see them, all of them the same size, as parts of one single story, like the comic strips she used to make, but without words. Or even more so, as words from a poem: clear and uncompromising but with an interpretation that is different for everyone. Because, as Oscar Wilde said, ‘All art is at once surface and symbol. Those who go beneath the surface do so at their peril. Those who read the symbol do so at their peril. It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors.’

This drawing begins first with Van Zyl herself, when she is intuitively attracted by images that are both charming and hard. A gladiolus, velvety and soft, with a viciously pointed bud; the disciplined beauty of feet in ballet slippers coupled with anxious tension; or the vagina that looks like a blossoming flower, while the sharp lines and the knuckles of a hand lend it a suggestive charge.

Drawing is a way to explore this fascination. A process in which she elevates the images above reality, evoking underlying associations that touch upon situations and emotions that cannot be captured in words or images. Too complex, too uncomfortable and too embarrassing to be depicted directly: ‘Tell me I’m living,’ wrote Louise Glück. ‘I won’t believe you.’

Esther Darley