Emma Talbot weaves everything together: memories and myths, dreams and reality, obsessions and poetry. Her drawings and sculptures are reflections of her subconscious, where all those impressions are stored away and often take on irrational associations.

In Woman – Snake – Bird, her second exhibition at Galerie Onrust, Talbot focuses on metamorphoses, transformations and transitions – from the material to the spiritual, from the human to the animal, the visible to the invisible – in order to get a grasp of the almost indescribable life force that can be found in them.

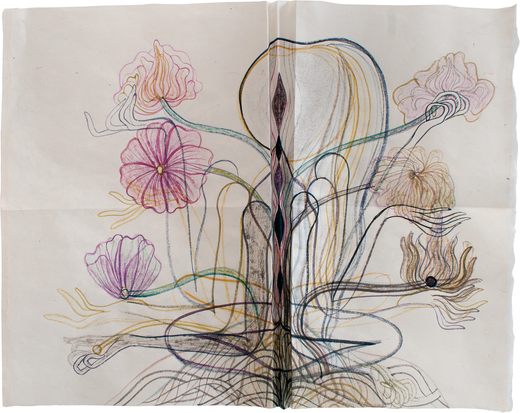

Her recent drawings on Japanese paper exude, above all, tranquility. Figures in yoga-like poses seem to withdraw or to transform. In fluid lines she draws spines in the form of life lines, junctions reminiscent of chakras, Brancusi's Endless Column or a stack of openings that could also be vaginas – another source of life and energy. Talbot leaves the interpretation undefined. She moreover creates, by way of folds in the paper, an intimate relationship with the viewer: the drawing that opens up to us like a personal letter or like a portable little medieval altar meant for private worship, which reveals a complete universe to that one particular user.

Alongside the subdued drawings, Talbot's sculptures come across as an overwhelming statement. As an impressive and imposing figure with broadly extended wings, Transformation: Woman-Bird gives rise to all sorts of associations. Its painted silk 'coat of feathers' brings to mind that of an magpie, and the twigs holding up the softly cascading material – the two being delicately and simply tied together – resemble the construction of a wing: both the ingenious character of this and its appearance as an aged, bony carcass. Beauty and decay, the ceremonial and the commonplace: magnificent as well as fragile. One is for sorrow, say the English on seeing a single magpie. But this one, ready to fly away to any destination, transcends the expression. Talbot takes inspiration from mythical narratives and creatures, and from the powerful auras of tribal masks and totempoles. Why does our culture emphasize, she wonders, the failure of an old woman? Why is wisdom translated into witchcraft and ugliness? Look at the sculpture of the serpent with a woman's head which, placed on a microphone stand, has been given a voice in the here and now. Here the woman as a demon is nowhere to be found. In fact Talbot seems scarcely aware of any negative connotation. A Slavic myth about a woman transforming into a serpent is, to her, mainly a symbol of unparalleled strength. "Use that strength! Rely on it," the works seem to call out.

With these sculptures Talbot creates shapes to which she can also relate in space. The sculpture as a stand-in, as an inverted self-portrait you might say. Without any moral or feminist implications, Talbot portrays an indescribable force. Energy which is being charged, at whatever cost and against any better judgment, by a kind of inner generator. Each work seems to be an attempt to gain control of the force that lies at the heart of every cycle of life; and each sculpture attests, in turn, to that life force.

translation: Beth O'Brien