Publication | Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing | Emma Talbot

February 20, 2021The Vitamin D3-featured artist tells us about the immediacy and freedom that she finds in works on paper, and what she listens to on her drawing marathons.

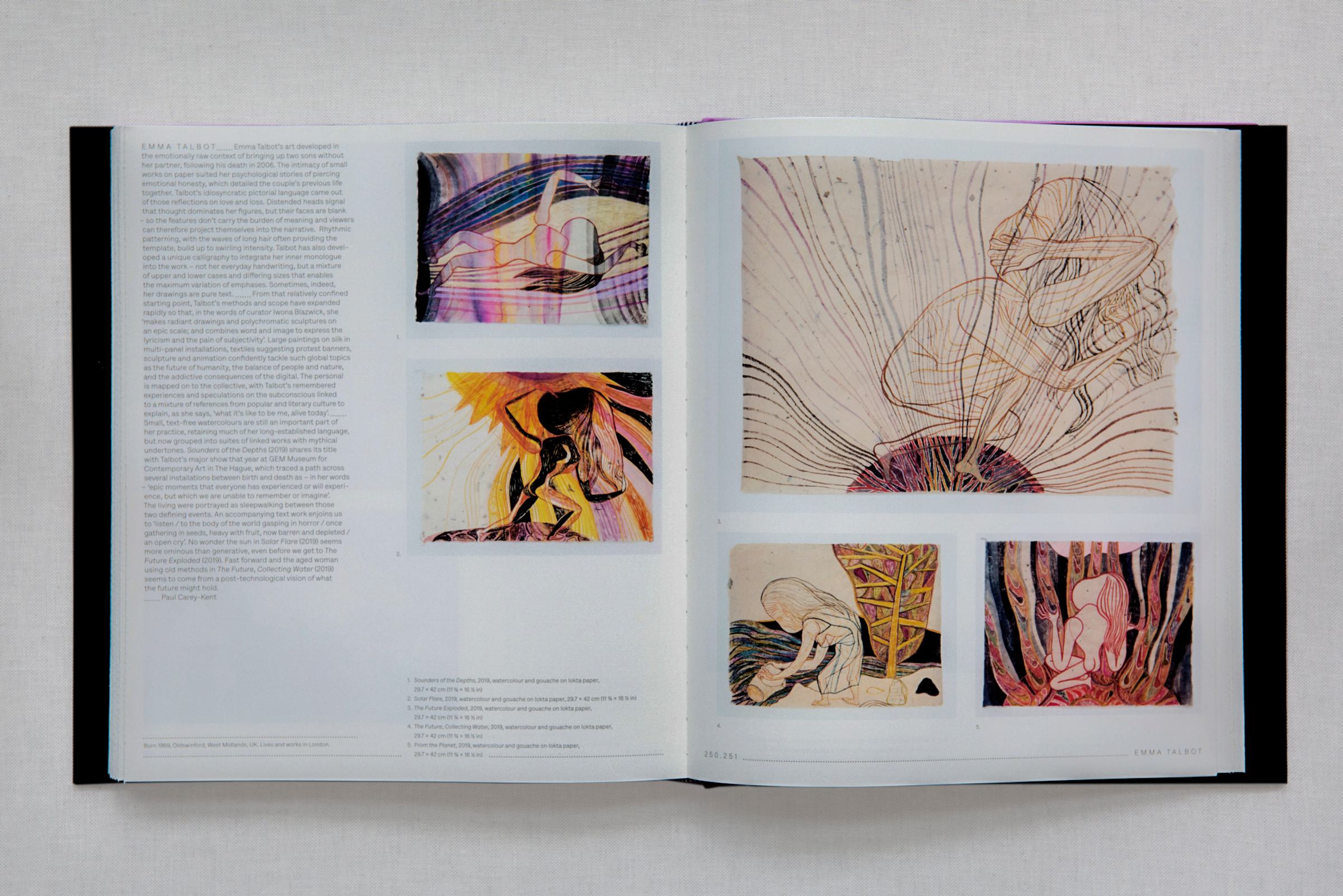

Emma Talbot’s art developed in the emotionally raw context of bringing up two sons without her partner, following his death in 2006. The intimacy of small works on paper suited her psychological stories of piercing emotional honesty, which detailed the couple’s previous life together. Talbot’s idiosyncratic pictorial language came out of those reflections on love and loss.

Distended heads signal that thought dominates her figures, but their faces are blank – so the features don’t carry the burden of meaning and viewers can therefore project themselves into the narrative. Rhythmic patterning, with the waves of long hair often providing the template, build up to swirling intensity. Talbot has also developed a unique calligraphy to integrate her inner monologue into the work – not her everyday handwriting, but a mixture of upper and lower cases and differing sizes that enables the maximum variation of emphases.

Sometimes, indeed, her drawings are pure text. From that relatively confined starting point, Talbot’s methods and scope have expanded rapidly so that, in the words of curator Iwona Blazwick, she ‘makes radiant drawings and polychromatic sculptures on an epic scale; and combines word and image to express the lyricism and the pain of subjectivity’. Large paintings on silk in multi-panel installations, textiles suggesting protest banners, sculpture and animation confidently tackle such global topics as the future of humanity, the balance of people and nature, and the addictive consequences of the digital. The personal is mapped on to the collective, with Talbot’s remembered experiences and speculations on the subconscious linked to a mixture of references from popular and literary culture to explain, as she says, “what it’s like to be me, alive today”.

Talbot is one of over a hundred contemporary artists featured in Vitamin D3: Today's Best in Contemporary Drawing, our new, indispensable survey of contemporary drawing. We sat her down and asked her a few questions about how, why and when she draws.

Who are you and what’s on your mind right now? I’m Emma Talbot. My work combines a number of elements - stylised figuration, hand-painted texts and pattern – I use a range of media, painting on silk, 3D forms, animation, sound and installation. I develop narratives that articulate the way the personal is entangled with the prevalent concerns of our time. Right now, I’m developing some narrative work that describes female figures having futuristic visions of post-pandemic, hopeful futures, where systems of power have been reconfigured.

What’s your special relationship with drawing and how would you describe what you do? Drawing is the basis for all my work. When I draw, I don’t pre-plan what I’m going to make, I try to download whatever I’m thinking in a very open, exploratory way. Drawing can articulate things seen in the mind’s eye, internal imagery, very effectively. There is something very special about the way drawing can capture imaginative imagery and fleeting thoughts. I make drawings without being too concerned about what I think of them. Over time, I see a subject appearing and follow that train of thought. Then I begin to research and develop my ideas.

Why is there an increased interest in drawing right now? Drawing was rethought in the 90s, both as a way of releasing it from being a preparatory activity towards more ‘substantial’ making and as a means of extending what constitutes drawing. Visual language and materiality have changed massively in the last twenty years or so and drawing still occupies an interesting space – both within the digital and as counter to the screen-based. What is most exciting for me is the prevalence of non-western, untaught, idiosyncratic makers that are gaining visibility – making extraordinary things.

What are the hardest things for you to get ‘right’? There is no such thing as ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. These aren’t useful terms. For me, it’s about my work conveying meaning. If I have a sense of the meaningfulness of what I’m making, then I believe in it. If it feels like it doesn’t have much meaning, it’s not exciting. My drawings are very immediate, I just let them happen without being concerned about whether they are ‘good’.

Is the immediacy of drawing part of its appeal for you? Yes. Immediacy eliminates doubt and I find that gives me a lot of freedom. I try to extend those principles into most of my work – to make things very immediately without changing or altering very much. I try to tune in to what I’m really thinking when I’m drawing and to be very directly honest about my thoughts, so my drawings often surprise me, by revealing things that are maybe unconscious.

Can you explain the difference between drawing as a child, something we can all relate to, and drawing as an artist - something most of us cannot? There’s something very absorbing about drawing as a young child, configuring a world as you’d like it – full of the things that hold your interest. This inventiveness often gets curtailed by the illusionary – usually when you’re a young teenager, when you start to impress others by drawing ‘realistically’ – from observation or from references like photos (or I guess stop drawing when you find you can’t easily achieve illusions). It took me a while to find my way back to the pleasure of inventive drawing as an adult, to release myself from concerns with good illusions or demonstrations of skill.

What do most people overlook when they attempt to ‘assess’ drawing? I don’t really know what others think or how they assess drawing. My observation is that the images that are considered ‘realistic’ in Western society are rooted in external imagery – usually things as observed in the world or as photographed/filmed. But the ways our brain constructs and returns imagery to us is very different. How we think and configure images internally (in our minds) supports our sense of the world, our idea of ourselves in the world, our ability to react and interact – but the mind’s eye is very inventive, associative, full of impressions and projections. I’m really convinced that the hand-drawn is the closest we can get to articulating the inventiveness of visual imagery in our minds.

When do you draw and what sort of physical, spiritual, mental or geographical place do you have to be in generally for it to work? I usually draw at home at a desk, listening to music, lectures, interviews or podcasts. I guess I get into a state of mind that is very relaxed; I really like drawing and I do it for hours. I draw anything I like. I do that for about three days at a time, and even though I produce lots of drawings, I usually feel like I haven’t really done anything. It’s only when I take the drawings to the studio that I start to see what I’ve got that interests me. It’s as if the movement to a different space transforms the drawings into something more definite.